Direction and Advice

To help public office holders comply with the

Conflict of Interest Act, the Office provides them with confidential direction and advice tailored to their individual situations. It continues to follow the processes developed since the coming into force of the Act and the interpretative approach taken by the Commissioner in the last two years to ensure coherence in the application of the rules set out in the Act. All public office holders must be able to feel confident the advice they are given is fair and appropriate. This is reflected in the Office's mission statement and is the objective of several projects within the Office's

three-year strategic plan.

Public office holders frequently consult the Office, either during or after their term of office. The Commissioner personally met with over 40 regulatees to discuss their personal situation, in addition to any communications public office holders had with their advisors.

Public office holders frequently consult the Office, either during or after their term of office. The Commissioner personally met with over 40 regulatees to discuss their personal situation, in addition to any communications public office holders had with their advisors.

They ask about a range of matters, such as how to arrange their affairs to comply with the Act, how to make a public declaration and how to meet their post-employment obligations. Questions about material changes accounted for one third of the requests for advice received in 2019-2020.

|

In 2019-2020, public office holders asked about

- gifts or other advantages (12%)

- outside activities (15%)

- post-employment obligations (20%)

- general obligations (21%)

-

material changes (31%)

|

Education and Outreach

The Office conducts a range of education and outreach activities to help public office holders understand and meet their obligations under the

Conflict of Interest Act. They supplement the confidential advice and direction provided to individual public office holders and other communications regarding compliance processes.

Information notices Information noticesThese educational tools explain how various provisions of the Act apply and, where relevant, the Commissioner's interpretations of them. All

information notices are posted on the Office's website and some are accompanied by videos which are also available on its YouTube channel, Ethics Canada.

| In 2019-2020, the Office issued 12 updated or new information notices: |

Presentations Presentations

Most are delivered in-person by the Commissioner and staff and six were delivered via teleconference. By using teleconference and webinar technology to deliver presentations, the Office can reach a greater number of regulatees.

| |

Social media Social mediaThe Office uses

Twitter (@EthicsCanada) to communicate directly with regulatees, for example by tweeting links to updated or new information notices.

| - The Office tweeted 171 times about its activities, role and mandate

|

Enforcement

While prevention is its major focus, the Office does not hesitate to apply the enforcement provisions of the

Conflict of Interest Act as appropriate.

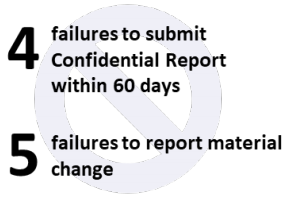

Administrative Monetary Penalties

The Commissioner can impose administrative monetary penalties of up to $500 for failures to meet certain reporting requirements of the Act within the established deadlines. These include Confidential Report filings, disclosures of material changes, firm offers of outside employment and their acceptance, and public declarations of gifts and recusals. In 2019-2020, the Commissioner did so in nine cases.

When a penalty is issued, the Act requires that the Commissioner make public the nature of the violation, the name of the public office holder and the amount of the penalty. Accordingly, the Office posts them in the public registry. It also makes reference to penalties on Twitter soon after they are added to the registry.

COMPLIANCE ORDERS

Under section 30 of the Act, the Commissioner may order a public office holder to take any compliance measure that the Commissioner determines is necessary to comply with the Act, such as submitting documents for the annual review, ceasing prohibited outside activities or divesting any assets that could give rise to a conflict of interest.

|

In 2019-2020, four administrative penalties were issued for failures to submit a Confidential Report within the 60-day deadline and five were issued for

failures to report material changes.

|

The Office faced an unprecedented compliance situation after the

Canadian Energy Regulator Act (CER Act), which established the Canadian Energy Regulator, became law in June 2019.

Sections 16, 22 and 29 of the CER Act set out the circumstances in which the Canadian Energy Regulator's chief executive officer, directors and commissioners, who are subject to the

Conflict of Interest Act as public office holders and reporting public office holders, are understood to be in a conflict of interest for the purposes of the

Conflict of Interest Act. They expand the meaning of conflict of interest beyond what exists in the

Conflict of Interest Act by prohibiting certain outside activities and holdings.

The Commissioner responded by issuing section 30 compliance orders to the Canadian Energy Regulator's chief executive officer, directors and commissioners to ensure they are not in a conflict of interest under the CER Act. This was the first time the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner had to issue a compliance order to ensure that public office holders comply with a broader definition of conflict of interest.

The Commissioner responded by issuing section 30 compliance orders to the Canadian Energy Regulator's chief executive officer, directors and commissioners to ensure they are not in a conflict of interest under the CER Act. This was the first time the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner had to issue a compliance order to ensure that public office holders comply with a broader definition of conflict of interest.

Examination Case Files

When the Office receives information about a possible contravention of the Act, including through media reports or complaints from members of the public, a case file is opened. The information is reviewed to determine whether the concern raised falls within the Office's mandate and, if it does, whether the Senator or Member of the House of Commons set out reasonable grounds to believe—or, in the case of a self-initiated examination, whether the Commissioner has reason to believe—that a contravention may have occurred. Some of these initial reviews lead to

examinations. In other cases, an examination is not found to be warranted and the files are closed.

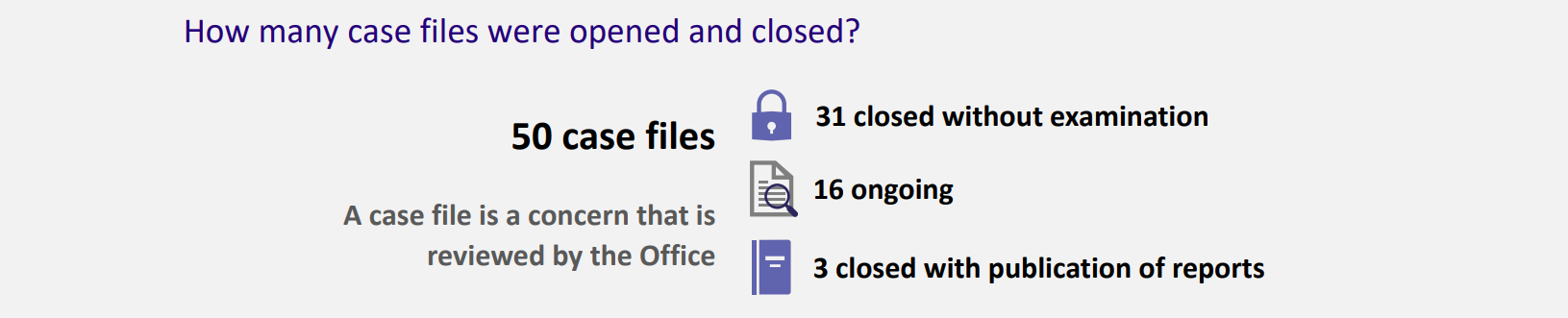

A case file is a concern reviewed by the Office. In 2019-2020, it reviewed 50 case files.

A case file is a concern reviewed by the Office. In 2019-2020, it reviewed 50 case files.

- 31 case files were closed without an examination

- 16 case files are ongoing

- 3 case files were closed with the publication of a report

|

|

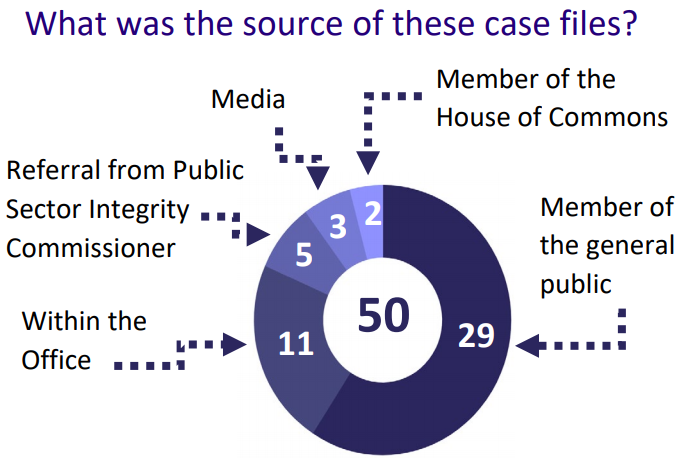

The Office reviewed these 50 case files based on the following sources:

- a Member of the House of Commons (2)

- the media (3)

- a referral from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner (5)

- within the Office (11)

a member of the general public (29)

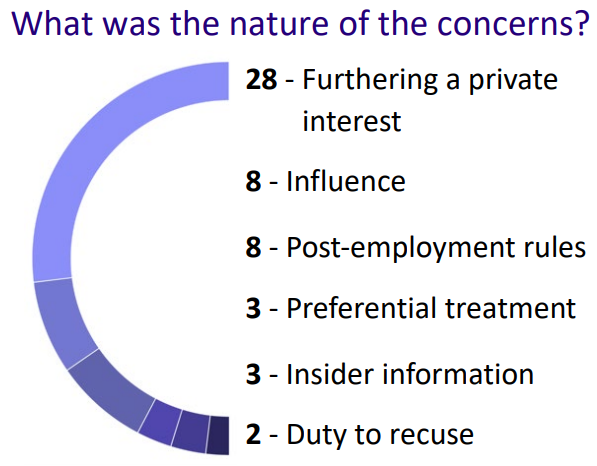

| The breakdown of the nature of these concerns is as follows: There were 28 concerns about “furthering a private interest."

There were eight concerns about “influence."

There were eight concerns about post-employment rules.

There were three concerns about “insider information."

There were two concerns about the duty to recuse. |

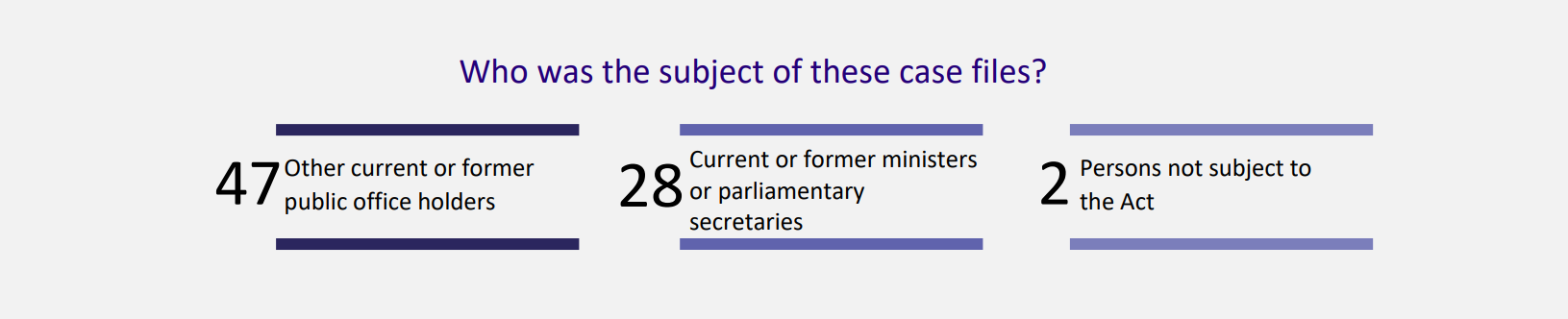

The subjects of these case files were as follows:

Current or former ministers or parliamentary secretaries were the subject of case files in 28 instances.

Other current or former public office holders were the subject of case files in 47 instances.

Persons not subject to the Act were the subject of case files in two instances.

Examinations

The Commissioner can launch an examination of a possible contravention of the

Conflict of Interest Act at the request of a Senator or Member of the House of Commons who provides reasonable grounds to believe the Act has been contravened.

The Act also gives the Commissioner the discretion to

conduct an examination on his own initiative if the Commissioner has reason to believe the Act has been contravened. Decisions to do so may be based on information that comes to the attention of the Office in various ways, including media reports and complaints from members of the public.

The Commissioner issues a

public report upon the completion of an examination. When the Commissioner decides to discontinue an examination launched in response to a request from a Senator or Member, a discontinuance report is issued.

Matters may also be referred to the Commissioner by the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner under subsection 24(2.1) of the

Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act. When such a referral is received, the Commissioner is required, under section 68 of the

Conflict of Interest Act, to issue a report, which is made public. The report must set out the facts in question, the analysis of the situation and the conclusion, whether or not an examination is launched.

In 2019-2020, the Office issued two examination reports under the

Conflict of Interest Act:

In the

Smolik Report, issued on May 30, 2019, the Commissioner found that Mr. Jim Smolik, a former Assistant Chief Commissioner and Acting Chief Commissioner of the Canadian Grain Commission, contravened two of the Act's post-employment provisions when he engaged in several interactions with the Commission on behalf of his new employer, Cargill Limited.

Mr. Smolik was found to have contravened section 33 of the Act, which prohibits former public office holders from acting in such a manner as to take improper advantage of their previous office. This rule applies for an indefinite period. The evidence showed he exploited his previously established Commission relationships and the knowledge and expertise he had acquired while employed at the Commission to help Cargill obtain a timely and favourable decision from the Commission.

Mr. Smolik was also found to have contravened subsection 35(2) of the Act. This provision prohibits former reporting public office holders from making representations for or on behalf of any other person or entity to any department, organization, board, commission or tribunal with which they had direct and significant official dealings during their last year in public office. Representations include communications made with a view to influencing official decisions, opinions or actions. For Mr. Smolik, this rule applied for a cooling-off period of one year following his last day in office. As a former Commissioner of the Canadian Grain Commission, Mr. Smolik had direct and significant official dealings with the Commission during his last year in public office. The evidence showed that an application by Cargill to the Commission, which was submitted by Mr. Smolik during his cooling-off period, was a communication made by him to the Commission with a view to influencing a decision or action.

In the

Trudeau II Report, issued on August 14, 2019, the Commissioner found that the Right Honourable Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, contravened section 9 of the Act when he used his position to seek to influence a decision of the Attorney General of Canada relating to a criminal prosecution involving SNC-Lavalin. Section 9 prohibits public office holders from using their position to seek to influence a decision of another person so as to further their own private interests or those of their relatives or friends, or to improperly further another person's private interests.

The decision in question was whether or not the Minister of Justice and Attorney General, the Honourable Jody Wilson-Raybould, should intervene in the Director of Public Prosecutions' September 2018 decision not to invite SNC-Lavalin, which was facing criminal charges, to negotiate a possible remediation agreement.

The Commissioner determined that Mr. Trudeau, either directly or through the actions of those under his direction, sought to influence the Attorney General's decision as to whether she should intervene in SNC-Lavalin's criminal prosecution. He further determined that Mr. Trudeau, through his actions and those of his staff, sought to do so improperly. The evidence showed that SNC-Lavalin had significant financial interests that would likely have been furthered had Mr. Trudeau successfully influenced the Attorney General. The actions that sought to further these interests were improper since they were contrary to the principles of prosecutorial independence and the rule of law.

The Office also issued a report as a result of a referral made by the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner:

In the

Wernick Report, issued on March 10, 2020, the Commissioner concluded that he did not have reason to believe that Mr. Michael Wernick had contravened the Act while he was Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet, and would therefore not pursue the matter further.

It was alleged that Mr. Wernick may have contravened section 9 of the Act in matters raised during the Trudeau II Report investigation. In that examination, the Commissioner concluded that the individuals who acted under the direction or authority of the Prime Minister could not have influenced the Attorney General simply by virtue of their position. This conclusion applied to a number of reporting public office holders, including Mr. Wernick.

Barring exceptional circumstances, the Office's target is to conduct examinations within a 12‑month timeframe.

As of March 31, 2020, the Office was working on 12 other examinations under the Act, 10 of which relate to the same subject matter. The nature of those examinations has not been made public. Four case files were also under review. The Office is often asked for information about examinations that are in progress, but strict confidentiality requirements set out in the Act prevent it from providing any information.

As of March 31, 2020, the Office was working on 12 other examinations under the Act, 10 of which relate to the same subject matter. The nature of those examinations has not been made public. Four case files were also under review. The Office is often asked for information about examinations that are in progress, but strict confidentiality requirements set out in the Act prevent it from providing any information.

The Commissioner believes the Act continued to work well in 2019-2020. He could, however, offer a few suggestions on possible amendments should Parliament decide to review the legislation.

Public Communications

In 2019-2020, the Office continued to undertake a range of public communications initiatives. They are aimed at educating and informing regulatees, as well as the media and the general public, about Canada's federal conflict of interest regimes and the Office's role in administering them.

The Office started developing a communications approach that identifies a range of actions in support of one of the key priorities identified in its strategic plan: building and improving communications and outreach processes.

Website Website

|

66,870 visitors

|  Social media Social media

|

1,245 followers

|

In October 2019, the Office launched a new

website aimed at better educating and informing regulatees, the media and the public. Designed to make information more easily accessible in the interests of transparency and accountability, it has improved functionality and is more mobile-friendly, making it a more effective source of information.

| Twitter (@EthicsCanada) is used to communicate information about the Office and its work. Items of interest to the Office and the ethics community at large, such as relevant reports from other Canadian conflict of interest commissioners and international organizations, are retweeted. In 2019-2020, the number of followers grew by 22%, increasing the Office's social media reach. The new communications approach includes a detailed social media plan.

|

Media and public inquiries Media and public inquiries

|

175 media

1,608 public

|  Presentations Presentations

|

11 presentations

584 participants

|

Recognizing the important role the media play in promoting awareness of the Commissioner’s role and mandate and the need to help them report as accurately as possible, the Office has continued to provide them with as much information as it is permitted to. It issues media advisories and

news releases and shares information via Twitter in addition to responding to media and public inquiries. The Commissioner participated in six interviews with journalists in 2019-2020.

| The Commissioner and representatives of the Office give a variety of

presentations to help Canadians and international audiences understand the role and mandate of the Office. Where possible, participants have access to an Internet-based audience interaction tool that enables audience members to use their mobile devices to anonymously ask questions and participate in live polls.

|

In May 2019, a senior representative of the Office gave a presentation to The Many Facets of Parliament event for parliamentary employees. In October, the Commissioner met with Parliamentary Internship Programme participants and led a discussion with political science students at the University of Ottawa. The Commissioner also gave presentations to Ontario Legislative Internship Programme students in December, and to a class at Carleton University in February 2020. That same month, he participated in the Conference Board of Canada's Public Sector Leadership Conference.

The Office receives a large volume of inquiries from members of the public. When responding, it takes the opportunity to educate them about the

Commissioner's role and mandate. When their concerns do not fall within the mandate of the Office, they are directed to other organizations that might be better able to assist them.

The Office received 1,783 communications from the media and the public in 2019-2020. The Office strives to respond to such communications in a timely manner and has established service standards to do so. The target for achieving those service standards was set at 80%. Media requests were responded to within four hours in 86% of cases. Communications from members of the public were responded to within two weeks in 80% of cases.

In 2019-2020, in support of its values of equality, respect and inclusiveness, the Office started using gender-inclusive language in its communications.

Collaboration and Best Practices

The Office continued to work with counterparts in Canada and other countries in 2019-2020, exchanging information about conflict of interest rules and practices and discussing related issues in order to stay abreast of evolving concerns and new developments in the field.

Domestic Outreach

In September 2019, senior Office representatives attended the annual meeting of the Canadian Conflict of Interest Network (CCOIN), held in Regina, Saskatchewan. Formed in 1992, CCOIN is made up of conflict of interest commissioners at the federal level and from all Canadian provinces and territories. The Office has coordinated information gathering for CCOIN since 2010.

|

|

In February 2020, the Office hosted a working meeting with the Quebec Ethics Commissioner and members of her staff. Employees in all divisions participated in briefings about Office activities and approaches in compliance, investigations, communications, strategic planning and other areas.

|

|

The Office has continued to implement the March 2018 memorandum of understanding that the Commissioner signed with the Commissioner of Lobbying to cooperate on education and outreach and to jointly organize educational activities for individuals affected by the work of both offices. In 2019‑2020, the two commissioners cohosted six teleconferences in which a total of 292 public office holders participated. Two teleconferences, one in English and the other in French, were held with reporting public office holders on their post-employment obligations in November 2019. These were repeated in January 2020 for those who were unable to participate earlier. In March 2020, separate English and French teleconferences were held for ministerial staff.

The Commissioner meets regularly with other agents of Parliament to discuss common challenges and ways of meeting them and to listen to presentations of interest to all. Likewise, Office employees liaise with their counterparts in the offices of other agents of Parliament. For example, staff in the Communications, Outreach and Planning division attend regular meetings of an agents' communications group. Staff in the Legal Services division are part of an agents' legal services group that organized a one-day seminar in May 2019 for all lawyers in those offices.

International Outreach

In 2019-2020, the Office remained active in the network of conflict of interest and parliamentary ethics organizations within the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. The Réseau parlementaire, which the Commissioner helped found in 2018, seeks to foster the sharing of best practices among commissioners and other ethics and conflict of interest bodies. In October 2019, a senior Office representative attended a meeting of the group in Namur, Belgium.

In December 2019, a senior Office representative made a presentation on the Commissioner's behalf at the 7th Global Conference of Parliamentarians Against Corruption. The event, organized by the

Global Organization of Parliamentarians Against Corruption, took place in Doha, Qatar.

In December 2019, Office representatives attended the annual conference of the

Council on Governmental Ethics Laws (COGEL) in Chicago, at which a senior Office representative participated in a panel discussion about compliance communications. COGEL is a U.S.‑based, international not-for-profit organization of government ethics practitioners. The Office is a member and other Canadian conflict of interest and integrity offices are also active in it.

The Office was scheduled to participate in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's

Global Anti-Corruption and Integrity Forum in Paris in March 2020, but the event was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

International counterparts sometimes approach the Office to organize delegation visits. During such visits, the Office provides an overview of the Canadian ethical framework and explains the role and mandate of the Office. They are also an opportunity for the Office to learn firsthand about the ethics regimes in other countries. In December 2019, it hosted a delegation from the Ministry of Personnel Management of the Republic of Korea.

|

|

Contacts with Parliament

The Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner is an independent officer of the House of Commons who reports directly to Parliament, through the Speaker of the House of Commons, on behalf of Canadians.

The Commissioner is required to submit an annual report on the administration of the

Conflict of Interest Act to Parliament by June 30 for tabling with the Speakers of the Senate and the House of Commons. He reports on examinations under the Act to the Prime Minister.

The Commissioner also testifies before parliamentary committees about the Office and its work. On May 16, 2019, he appeared before the House of Commons

Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics about the Office's budgetary submission for the 2019‑2020 Main Estimates. The Committee has oversight responsibility for the Office and reviews its annual spending estimates, as well as matters related to reports under the Act.

The Commissioner had been invited to appear before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics in March 2020. However, the committee meeting was delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our tools

The success of the Office's mission is supported by its people and its infrastructure. Because the Office is a small organization, it has the flexibility to respond quickly to changes in the external environment.

Our People

The accomplishments of the Office depend on the hard work and dedication of employees at all levels. Commissioner Dion has complete confidence in the senior management team and indeed in all Office employees. They produce work of consistently high quality, demonstrate rigour and professionalism and act with integrity at all times.

The Commissioner is a separate employer whose employees are not part of the federal public administration. The Office has its own terms and conditions of employment relating to hours of work, employee benefits and general working conditions affecting employees, and they ensure that all reasonable measures are provided for their safety and security. The terms and conditions of employment were updated in 2019-2020 to ensure they are in line with those of other parliamentary entities and the federal public service.

The Office shares similar values with the public service and parliamentary entities. All Office employees are expected to follow the values—respect for people, professionalism, impartiality and integrity—set out in the Office's

Code of Values and

Standards of Conduct. These key documents were also updated in 2019-2020.

The Quality Workplace Promotion Committee continued to coordinate initiatives to promote employees' well‑being. These included a two-day mental health first aid course offered by the Canadian Mental Health Association; participation was mandatory for directors and managers. The course was to be held twice in order to accommodate all participants, but the second session was postponed because of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

our Infrastructure

The Office has a sound internal management framework in place to ensure the prudent stewardship of public funds, the safeguarding of public assets and the effective, efficient and economical use of resources.

Because the Commissioner is an independent officer of the House of Commons and the Office is a parliamentary entity, it is not generally subject to legislation governing the administration of the public service or to Treasury Board policies and guidelines. It tries to ensure that its resource management practices are, to the greatest extent possible, consistent with those found in the public service and in Parliament. The Office also looks at policies and practices of other parliamentary entities and generally follows what they do, unless there is a valid reason to take a different approach.

The Office's financial statements are audited each year by an independent external auditor. The Financial Resources Summary appended to this report outlines its financial information for the 2019‑2020 fiscal year.

In March 2020, the Office organized a two-day occupational health and safety training course for its Work Place Health and Safety Committee and employees whose duties and responsibilities have an occupational health and safety component.

Finally, to support efforts to limit the spread of COVID‑19, in March 2020, the Commissioner suspended in-office operations and assigned all staff to telework. Thanks to measures put in place earlier and support from the House of Commons information technology group, the Office was well equipped to continue to achieve its mission under modified working conditions. Measures completed in 2019-2020 included the replacement of remaining desktop computers with laptops and tablets and the development of a pilot telework policy.

|

The Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner comprises the following divisions: - Commissioner's Office (4 employees)

- Advisory and Compliance (19 employees)

- Investigations and Legal Services (8 employees)

- Communications, Outreach and Planning (8 employees)

-

Corporate Management (11 employees)

|

Our challenges

External developments can impact the way the Office implements its mandate. All of these challenges are opportunities that carry the potential for positive change.

SAFEGUARDING THE PUBLIC TRUST

Gaining and retaining public trust remains an ongoing challenge for institutions in Canada. This is evidenced by data published by credible international organizations that provide a broad indication of levels of public trust in Canada.

Transparency International's

Corruption Perceptions Index ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. In the 2019 index, Canada ranked as the 12th least corrupt country in terms of public perception, three positions behind its 9th place ranking in 2018.

Transparency International's

Corruption Perceptions Index ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. In the 2019 index, Canada ranked as the 12th least corrupt country in terms of public perception, three positions behind its 9th place ranking in 2018.

The

Edelman Trust Barometer is an annual survey that explores trust in business, government, non-governmental organizations and media across 28 global markets. According to its latest edition, released in February 2020, public trust in Canada slipped just below the global average in the past year.

Although overall trust levels have dipped slightly, these results demonstrate that Canadians place a great deal of importance on the integrity of their institutions.

Transparency and public trust interact in complex ways. In a democratic society, the latter cannot exist without the former. Yet when transparency allows light to be shined on instances of conflicts of interest, no matter how minor they might be, the public trust tends to erode. At the same time, the more issues of public integrity become salient, the better the public understands that safeguarding democratic institutions is a perpetual endeavour.

It is encouraging to note that more than half of the concerns the Office reviewed in 2019-2020 came from the general public. There are advantages in harnessing public scrutiny to strengthen the Office's compliance mechanisms. After all, the public has the most to lose when the checks and balances of democracy are not respected. Hence, the Office will continue to improve its outreach and education to ensure Canadians have the tools and understanding necessary to participate in safeguarding the public trust.

effective oversight

The Office can administer the

Conflict of Interest Act and the

Conflict of Interest Code for Members of the House of Commons more effectively when public office holders and Members of the House of Commons reach out to the Office before taking actions or engaging in activities that could potentially lead to a contravention of the applicable regime. Such knowledge could enable the Office to direct and advise them on how to deal with those situations in order to maintain compliance and avoid any loss of public trust.

While the Office has come across information indicating potential contraventions from time to time, it has not historically conducted any active oversight. Such information also allows the Office to apply the regimes' enforcement provisions as appropriate.

In 2019-2020, initial steps were taken to staff a new data analyst position in the Communications, Outreach and Planning division to help the Office improve its oversight. Monitoring of sources of public information will be conducted, particularly for positions that have been evaluated as potentially having a higher risk of conflict of interest.

The need to ensure effective oversight has become even more important as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In such an extraordinary situation, complying with the Act and the Code may, understandably, not be top of mind for public office holders and Members.

Court Matters

Matters involving the Office have been the object of several applications for judicial review. While dealing with them can consume a significant amount of Office resources, they can also be opportunities to clarify the Commissioner's mandate and powers.